The site of Abila (modern name: Qwailibah or Qweilibeh قويلبة ) is probably the less-known classical site of Jordan. It was nevertheless a city that gained its position within the famous Decapolis league, this Hellenistico-Roman network of "westernized" cities scattered between the today South Syria, Jordan and Palestine. Those cities, among whose we count Jerash, Um Qais and Pella, increased their prosperity under the Roman Empire and the Byzantine period. They offered to their inhabitants the comfort of a western lifestyle.

Abila is nested in a fertile wadi descending to the Yarmouk valley, 13 km northeast to Irbid. A perennial spring waters the olive and pomegranate orchards and probably represented one of the favourable conditions that leaded to the occupation of the site starting from 4000 BC. The heart of the classical city extended on the western slope of the wadi, while the eastern side contains a subterranean cemetery with numerous painted hypogea, a unique and highly valued archaeological treasury for Jordan.

Far from being unattractive, the site is unfortunately disadvantaged by several factors that maintained it in overlooked and threatening conditions. In a country where the heritage preservation is motivated by the tourism resources potential, Abila is suffering from its relative proximity with Um Qais, better managed for the welcome of the mass tourism. Abila lays isolated, away from the classic tourist circuits. Except the regular presence of a guardian, nothing akin to a management plan has been implemented for the protection, the conservation and maintenance of the site, letting the archaeological remains exposed to erosion, weathering and looting. The finest tomb of the hypogeum has been totally ruined by the robbers, and this after the excavations. Moreover, the few excavations conducted on the site of the ancient city present a regrettable lack of methodology and a doubtful professionalism that threatens the conservation. The reconstruction carried out on the Christian monuments unfortunately shows a botched work, with use of concrete and even silicon. Scientific documentation is almost inexistent concerning the excavations of the city as well as for the reconstruction work. In contrast, a certain number of tombs of the subterranean cemetery have been carefully surveyed and documented (but the documentation is still waiting digitization).

However, in spite of those handicaps, Abila will surely charm the travellers who enjoy discovering picturesque and almost unexcavated site, as the 19th or early 20th century explorers did. This has a touch of romanticism, maybe the only little boon that we can see in this situation of abandonment. It is yet an antic classic city that lays underground, with theoretically all the typical elements that characterizes a self-respecting romanised town. But the singularity of Abila is that, due to the topography, the urban plan seems to follow no rule. The elements are set in a totally unusual organization. Some of them are even still to be discovered.... or play with the mystery. The urbanization developed according to the irregularity of the relief and the land configuration puts Abila closer to Pella than to Jerash or Um Qais. |  |

Abila site was occupied almost without interruption since the Chalcholithic or Bronze Age till the Mameluke period (though its use during this later period was limited), which means that this site has one of the longest occupations in Jordan (from about 4000 BC till 1500 AD). It is absolutely certain that the reuse of stones extracted from the collapsed buildings of the preceding culture was largely practiced, so that the interpretation of the urban structures at specific periods becomes challenging. This could eventually be one of the reasons why we did not find (yet) the temple. Moreover, the city was destroyed by the earthquake of 746 AD.

Abila reached its peak during the Greco-Roman and Byzantine ages and is mentioned by the ancient authors under different names: Abila, but also and mainly Seleucia (and eventually Raphana). The city was effectively captured by the Seleucid Antiochos III. While a tradition attributed the city's origin to Alexander the Great himself, it is probably the Seleucids who shaped and developed the city over a previous settlement, while they also hellenised the North Jordanian region. Abila fell for a short period in the hands of the Hasmonean Alexander Jannee, who annexed several hellenised cities to the Jewish kingdom. In 63 BC, the region falls under the Roman rule and Abila become a freed city able to gradually gain its prosperity. Abila won its place in the Decapolis, even if the city does not appear systematically in all the Decapolis cities lists. It is possible that it took a certain time for reaching the necessary prominence to get this prestigious status. The city effectively seems to become wealthy mainly at the Late Roman period and never benefited from imperial largess for financing the public buildings as Jerash did. This could explain why it is not systematically mentioned as a Decapolis city by the ancient historians. Nevertheless, like most of the Decapolis cities, Abila minted coins between the 2nd and the 3rd century AD, under the name of Seleucia Abila. The following example is a bronze coin minted during the rule of Elagabalus (218 - 22 AD) showing on the verso a monumental temple and two towers. This regular representation of a temple with 2, 4 or 6 columns on the Abila's coins remain mysterious. Other coins also portray the deities of Herakles, Athena and Tyche. In the classical Antiquity, the worshiping of such deities automatically implicates a cultic structure that remains unfindable till now. Moreover, certain coins identify Abila as a "city of asylum". Yet, the asylum customs in Antiquity suppose the existence of a sacred area, with temple and temenos, where the refugees can stay safe.

A.Lichtenberger art., ref. below

A.Lichtenberger art., ref. below

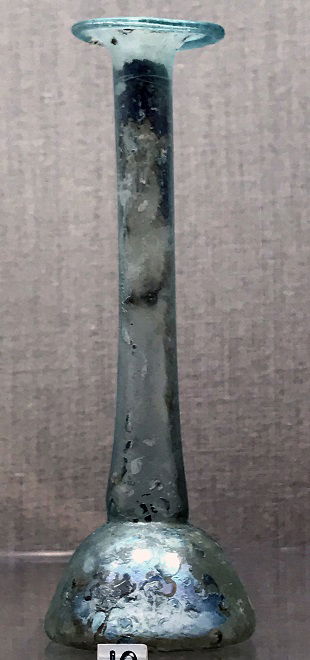

Abila site witnessed an important agricultural activity. The exploitation of the water spring by aqueducts is already attested for the Iron Age. The city had also an industrial activity, especially in glass manufacturing. The high prosperity level evidenced by the richly decorated tombs shows that Abila was part of the large commercial and cultural network that linked the cities of that area and held an integrated position that has nothing to see with its today isolation. At the Christian time, Abila was even an episcopal see. The below picture show a glass chandelier (5th AD) found in one of the churches:

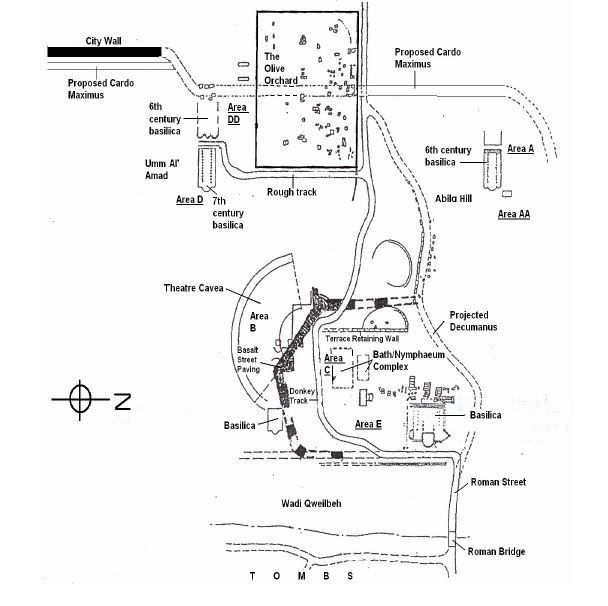

The site on the western slope of the wadi mainly consists in two hills linked by a saddle: Tell Abila on the north side is an elevation that contains the most ancient traces of a permanent settlement (starting from the Bronze Age) and was probably an acropolis at the classical period, before offering space to a large Byzantine church. Tell Umm El Amad is located in the orchards more to South and exposes the remains of two churches, with reconstituted columns.

|  |

The hills are connected by an ancient straight road. We could interpret it as a kind of Cardo (or Decumanus), however it doesn't appear plausible that this axis had played the real role of a Cardo, along which we should normally find all the main public buildings of a Roman town, unless a whole undiscovered part of the city extended to the West, behind the tells. Between the hills extends a saddle area that stoops down to the wadi. The city probably ranged downhill in terraced levels. In its lower part (down-town), we find confusingly road sections, baths and fountains with important water channel outlets, habitats, a possible theatre (?) pinned in a road corner, the remains of an eventual monastery.... near the bottom stand the vestiges of a cruciform basilica, with reconstituted columns. A bridge leads to the opposite slope of the wadi. The eastern side is apparently free from urbanization and was the domain of the deceased. However, we also find tombs on the western slope, north to the urban centre.

Such a plan leaves us quite stunned. While some main classical structures are effectively recognizable (nymphaeum, baths, section of street and maybe a theater), some others are strangely missing, unless undiscovered so far: no trace of any temple, in spite of the fact that the coins minted in Abila reveal an impressive temple. A monumental statue of Artemis was even found on the site. We also don't know where could be the market place and other public areas. In addition, the accumulation of usually imposing buildings in the restricted area of the saddle bottom challenges the representation the town... what this city could look like? According to the richly painted tombs of the Late Roman period, Abila inhabitants were wealthy and their city should have been more significant than the bunch of structures stacked in the bottom of the saddle. Only systematic investigations could answer those questions and bring a better understanding of the urban development of Abila and its evolution over time. Unfortunately, the excavations are conducted in broken lines and incompletely. Due to religious motivations, the archaeologists mainly focused on the Christian vestiges. Here below is the supposed plan of the city, areas A and D being respectively Tell Abila and Tell Um Al Amad:

C. Bennett, T. Rathjen art., ref. below (2004)

C. Bennett, T. Rathjen art., ref. below (2004)

The streets and the bridge

| When we overlook the site from the area of Tell Umm-Amad, the most striking element is the basalt avenue leading through the down-town to uphill. It reminds us the famous Cardo of Umm Qais. However, it is very unlikely that it was a Cardo as, following the archaeologists, it dates to the Byzantine period. It crosses over a smaller straight limestone street that seems to lead to the baths and nymphaeum complex and dates to the Roman period. We could carefully suppose that the basalt avenue is eventually built over an earlier Roman street going through the down-town and up till to Tell Abila. More extensive researches should be conducted in order to understand the streets system of the city and therefore its whole urban organization. |

| |

The bridge over wadi Quwailibah, linking the necropolis to the town, dates to the Late Roman period, according to the archaeologists. The pavement that we see today on its top could be, as well as the basalt avenue that apparently prolongs the bridge, from the Byzantine period. It overlays a smaller structure of an earlier period, the basement of which is embedded in the ground at a depth of 5 m, following the probe excavations. This means that an original structure crossing the river at a lower level has been heightened at a later period, in order to facilitate the carts traffic and ovoid the pedestrians to walk down for crossing. This bridge was more impressive than it is today. The erosion has considerably filled up the bottom of the wadi. Further works would be needed in order to have a clear idea of this construction. |  |

The baths and the nymphaeum

A large hydraulic complex is located in the down-town, only partly excavated. Large water channels end up under a vaulted structure that could be part of a nymphaeum, a monumental fountain. The vaulted arch was covered with painted plastered. The size of the water channels let suppose that profuse flowing water was used in the complex. Abundant Water use and bathing represent a preponderant characteristic of the Roman lifestyle and are largely attested in the Decapolis cities. Those underground aqueducts drew the water from a copious local spring along the western slope of the wadi Quweilibah. The oldest section of them dates back to the Iron, Persian and Hellenistic periods. Those water supplies could provide water to 8000 to 10000 persons, completed by the collection of rain water gathered in cisterns. They also could eventually be connected to a very extended underground aqueducts network bringing water from South Syria till Umm Qais, called the Qanat Firaoun.

|  |

The theater

The theatre is still to be found. Some archaeologists see in the curved topography of Tell Umm-Amad's downhill the cavea of a theatre. Probe excavations were initiated at the corner of the basalt avenue, but nothing till now can confirmed that the remains are effectively the foundations of the theatre. Contrariwise, the exposed structures seem to date to the Byzantino-Omayyad period, with evidence of collapse from the hill. The so-called "cavea" is maybe the result of a landslide... we can moreover argue that the location seems very strange for a public monument such a theatre... nevertheless, the published site maps mention this area as being a theatre, waiting for further confirmation...

|  |

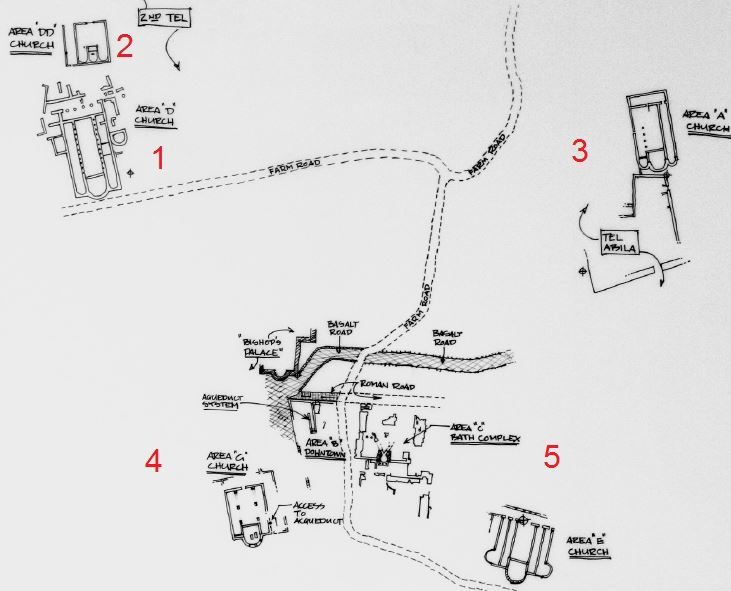

The churches

The churches definitely represent the most eye-catching monument of Abila site, essentially because they gained the favour of the archaeologists. Abila was even a Christian episcopal seat called Abila in Palaestina, which confirm the predominance of the city at the Byzantine time. Evidence has shown that the site was used for Christian worship from at least the seventh- to eighth-century. The site counts 5 churches:

D.Chapman art, ref. below

D.Chapman art, ref. below

1) The most recent church, located on Tell Umm-Amad, dated to the 7th - 8th centuries, with a probable reuse of elements from an earlier building. The late date of this church reveals that the Christian cult was still practiced at the early Islamic period. This triple-apsed construction was probably majestic, with alternate black (basalt) and white (limestone) columns. The columns have been rebuilt, unfortunately with a poor methodology. However, at the first look, the view of those standing columns is particularly charming when we reach the site from the West. The floor of the church was compound of differently coloured stones in checkerboard pattern. A huge cistern associated with this building lies north.

|  |

2) The remains of a smaller church, dated to the 6th century, can be seen behind the main church. We do not have details about it...

3) The Tell Abila church has also with three apses. The building is dated to the 6th century. It was previously supposed that the construction would recover the basement of an ancient Roman temple, but surprisingly, the remains laying underneath are from the Bronze Age, not from the Roman period as expected. Despite of the presence of Roman pottery sherds around the church and portions of a statue of Artemis found in the north side, the archaeologists couldn't confirm the existence of the Roman temple at that place, that yet should have been the acropolis of the city. However, a monumental Roman building with an atrium was discovered on the western area of the tell, under the byzantine strata. We miss details about the interpretation of that building.

4) A small church is located on the foothill of Tel Umm Al Amad, overlooking the wadi. We do not have details about it...

5) A large cruciform church is located in the low part of the site. This building was extensively excavated by the archaeologists. They discovered beautiful mosaic pavements laying about 1 m deep under the actual ground level of the church (the mosaics are covered for protection). Unfortunately, no publications of those floors are accessible to the public except in this video: (after the 42nd min.). There is till now no explanations to this duplication of ground-floor levels. It is like if there were two churches built one over the other one. Four burials have been found between the levels, but the faces of the bodies were turned toward Mecca, which let assume that they were Muslim. The presence of a mihrab in the south wall of the church indicates that the building was turned into a mosque in early Islamic period. Thus, it is unclear if the upper structure, even shaped as a church, was really used as a church and if yes for how long..., or should we eventually see a mosque that reuse a church basement...This hypothesis could explain why the lower basement has been replenished by a dirt layer in order to build a second structure, as well as the presence of the Muslim burials. Accurate researches should be conducted to determinate the chronology of those levels, the date of the burials, and also take in consideration the destruction of the site by the 746 earthquake. As for Tell Umm-Amad church, the columns reconstitution, although eyes-catching, was not conducted with accuracy.

https://www.wmf.org/project/abila

https://www.wmf.org/project/abila

The hypogea

Abila's necropolis constitutes the strongest interest and value of this site for the Jordanian heritage. Romano-Byzantine rock-hewn necropolis with loculi (niche hewn in the walls) tombs are well represented in north-western Jordan and especially around Irbid area. A large number of urban and rural settlements preserve such funerary monuments and probably many hypogea still wait to be uncovered. We find subterranean cemeteries in Barsina, 15 km West to Irbid, or Yasileh, 7 km North-East to Irbid, in Beit-Ras Capitolias, 5 km North to Irbid... without omitting the other Decapolis cities as Jerash, Pella, Um Qais. Those tombs generally date back to the Roman, Late Roman and Byzantines periods, with frequent reuses over time. Some of them present very extensive subterranean burial chambers with a high concentration of graves and loculi. The below photos show some structures uncovered in Yasileh:

|  |

|  |

Z. Al-Muheisen, ref. below | |

The decoration of a familial vault was a privilege reserved to wealthy families. Therefore, we find precious tombs in priority around the urban settlements as the Decapolis centres, but also sometimes on minor sites. Beside the painted tombs of Abila and Beit-Ras, some beautiful specimen have been discovered in Maru (2 km East to Beit-Ras) and Som (10 km Northwest to Irbid).

Abila site counts hundreds of rock-cut tombs, essentially located on the eastern slope of the wadi, but also on the northern sector of the western side. Only a portion of them presents painted frescoes, but they give to the site of Abila all its value and specificity. The number of surveyed and documented tombs stands at 22, but other have been opened and then closed without survey or only quick record. Up-to-date reports are missing, after the detailed survey published in 1994 by A. Barbet and C. Vibert-Guigue. Except the fact that the tombs are closed to the public, this wonderful heritage is endangered by a lack of protection and preservation: the paintings are threatened by humidity, floods and even vandalism. Much of the ornaments in the tombs have been already lost, while the funeral material is dispatched. Yet, the rich burial culture of Abila would deserve to be shared with the public.

photo by author |  |

Tombs are dug in a calcareous stone crisscrossed by more resistant volcanic layers that sometimes hindered and conditioned the carvers. The run-off waters were collected through channels outside but also inside the monuments and captured into pits. Some monuments experienced collapsing already during their using time. It is interesting to notice that some cracks have been clogged and turned to decoration at that time.

http://users.stlcc.edu/mfuller/abila/abila2017/1231%20AE1996,%20H60%20pre-excavation.jpg

http://users.stlcc.edu/mfuller/abila/abila2017/1231%20AE1996,%20H60%20pre-excavation.jpg

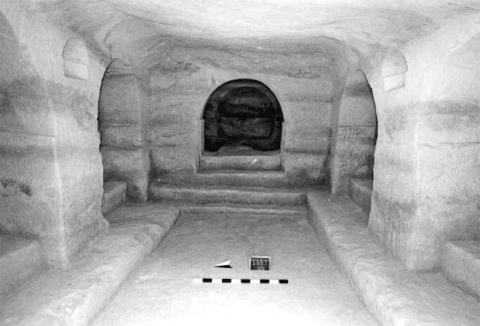

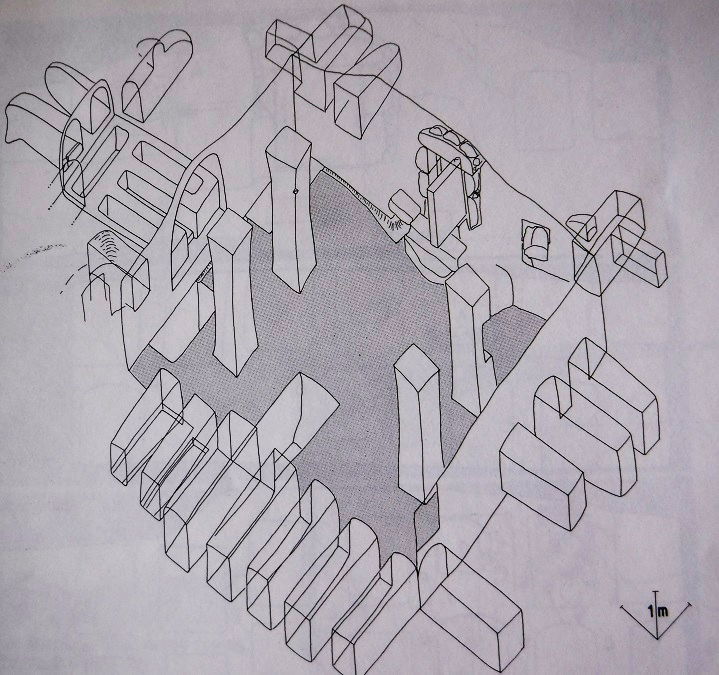

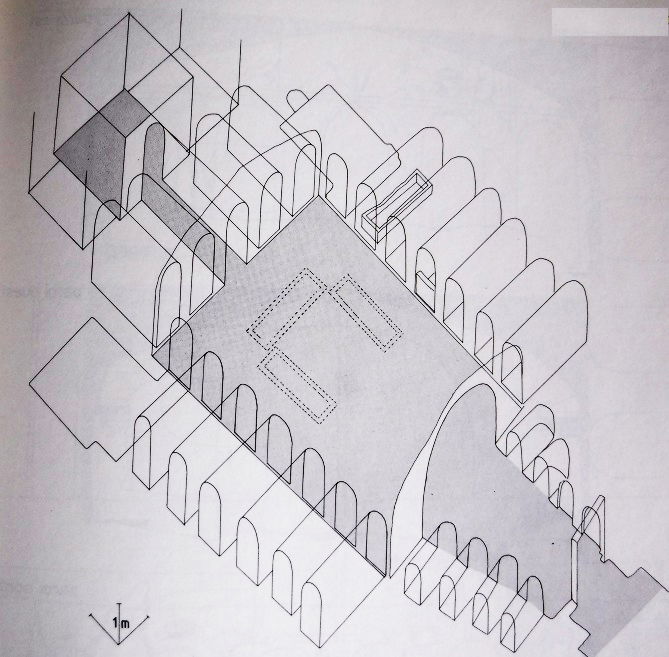

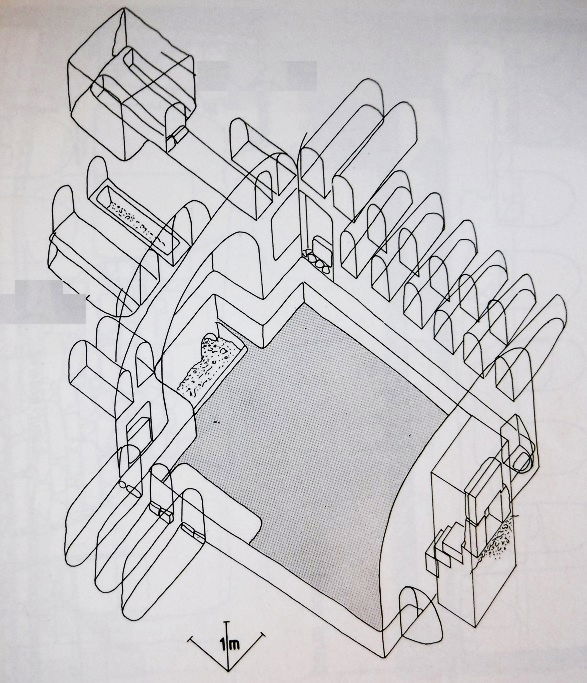

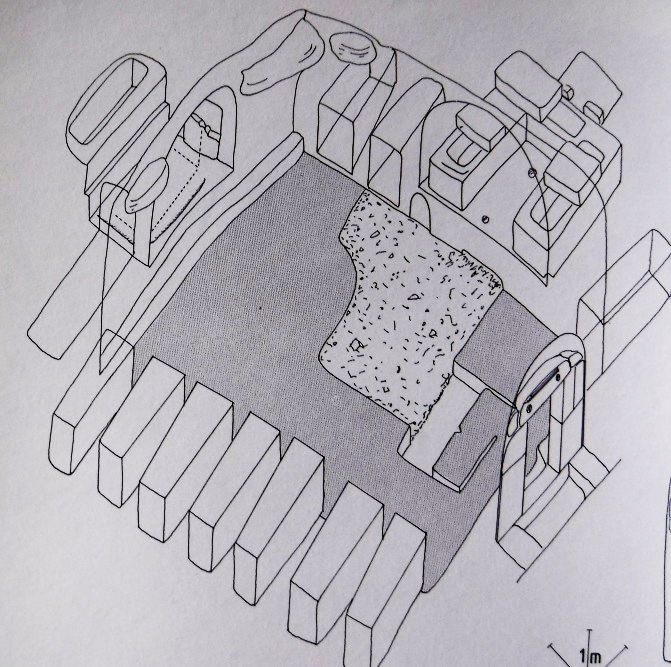

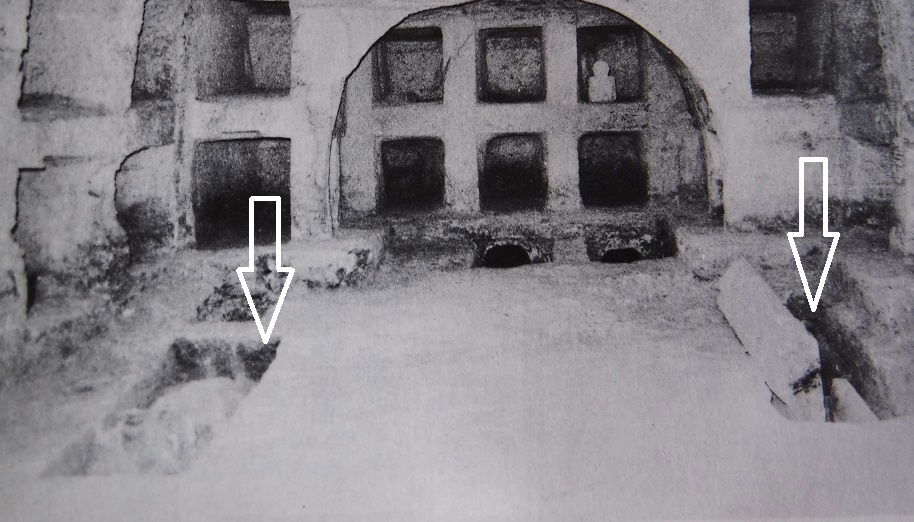

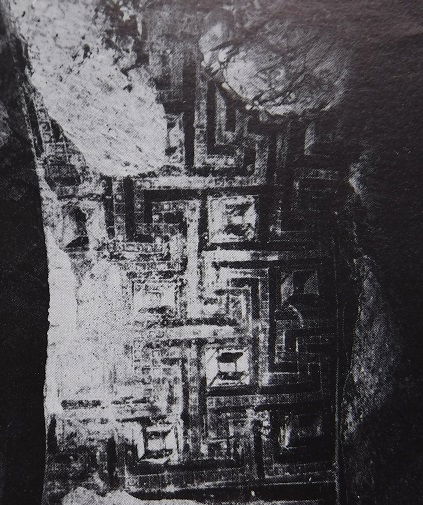

It exists several tomb structures in Abila: the general typology is a unique room with eventually an arched alcove (acrosolium) in the bottom and loculi dug in the lateral walls. But this scheme can have further elaboration: the chamber can contain several acrosolia, can be preceded by a kind of vestibule at the entrance, side annexes... Some tombs present two adjoining rooms, the second chamber being carved deeper inside the hill. The tombs are often clustered and collisions between monuments sometimes happened underground due to the contiguity of the walls. Later, the robbers took advantage of this promiscuity and had just to break the rock walls to pass from a tomb to another. The vaults capacities can reach several tens of places.

A.Barbet, C. Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol. II pl.7 |  A.Barbet, C. Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol. II pl.47 |

A.Barbet, C. Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol. II pl.75 |  A.Barbet, C. Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol. II pl.56 |

The orientation of the tombs (East-West or West-East) allowed a natural lighting at the sunrise and the sunset though the entrance, completed by the presence of oil lamps. The tombs were closed by heavy basalt doors, the design of which imitates the wood doors. Some specimens are still on place.

photo by author

photo by author

Following the customs generally practiced in the Near and Middle East, the burial type in the antic Jordan is the entombment (and not cremation as practiced in the western Roman empire). In Abila, some skeletons have been uncovered.

We find four burial types in Abila, as more commonly in the North Jordanian hypogea:

- the sarcophagi are transportable stone coffins. They are always carved in the basalt, a stone considered as precious. Therefore, they represent the most prestigious burial, but not the most common. However, we generally find at least one sarcophagus in each tomb, generaly laying in the centre of the chamber, or more seldom encased in a pit or a loculus. A wooden or leaden coffin containing the body was placed inside the basalt sarcophagus. Sarcophagi have plus or less elaborate ornaments, with typical wreaths, stylized flowers, lions heads but also sometimes portraits. The following richly decorated example was uncovered in one of the Abila tombs:

A.Barbet, C.Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol.I p.336

A.Barbet, C.Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol.I p.336

- the pits are dug in the ground of the chamber, along the walls and are generally 1 m deep. They can also be of small size for receiving children's bodies. They were covered by a slab. No specific decoration or honouring mark have been noticed for this kind of burial. However, pits may have sometimes received sarcophagi.

A.Barbet, C.Verbert-Guigue, ref. below vol. II pl.40

A.Barbet, C.Verbert-Guigue, ref. below vol. II pl.40

- the bedrock-sarcophagi are coffins carved in the stone along a wall, especially in the alcoves. They are similar to fixed sarcophagi and can present the same ornaments. In some cases, the bedrock-sarcophagi have been painted in black in order to imitate the basalt stone. They are closed by a slab.

http://users.stlcc.edu/mfuller/abila/TombBedrockSarcophagus.jpg

http://users.stlcc.edu/mfuller/abila/TombBedrockSarcophagus.jpg

- The loculi are cavities burrowed in the rock walls and can rank on two superimposed rows. They can have different sizes but are generally 2 m deep. Their opening can be squared or arched. Smaller loculi can eventually be found inside the walls of a loculus and were probably receiving the corpses of small children. The place foreseen to receive the body is often carved lower, with a stone cushion for supporting the head. Loculi are closed by a slab or an arrangement of small stone fixed with mortar. In some tombs, we see that spaces for loculi were foreseen in advance with drafts but have never been dug. The wall surface between and around the loculi often receive decorations with floral or architectural motives. We also see small niches foreseen the oil lamps.

photo by author |  |  |

A.Barbet, C.Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol.I p. 318 |  A.Barbet, C.Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol.II pl. III |

Archaeologists found a certain number of anthropological remains. We unfortunately do not have any study about the individuals and more generally the population found in the tombs. What is sure however, is that the tombs were subject to multiple reuses over time. This very common phenomenon would make a survey challenging. In general, the bones of the previous occupants were pushed aside to let space for the newcomer, so that when the archaeologists uncover a burial, bones and objects are upside down. Moreover, tombs robbers of course did not miss to pass by... It is quite exceptional to find a tomb with a single body in place.

|  |  |

|  |

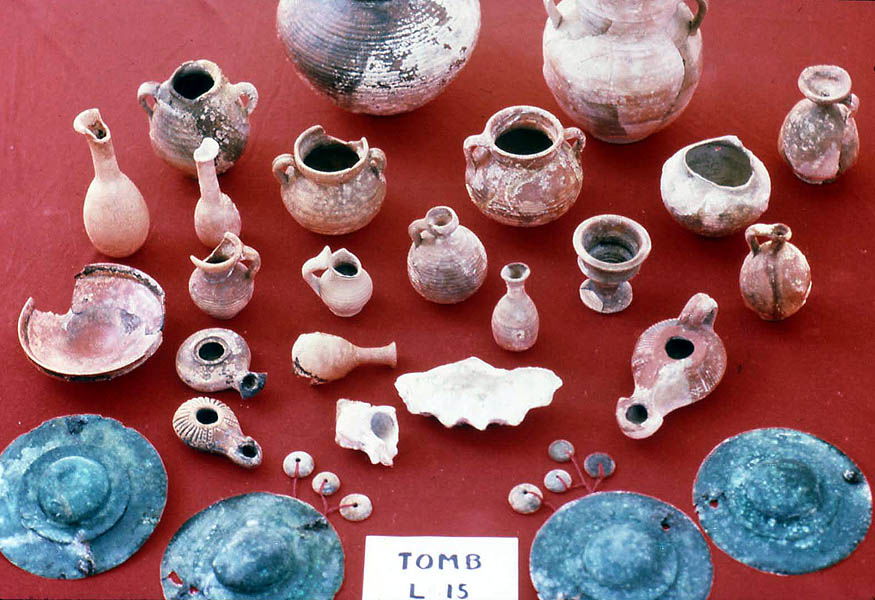

The tombs have provided a rich funeral material. Oil lamps are present in a large quantity, broken or intact, as well many glass flasks, potteries of different sizes, jewels, coins and some figurines.... the lamps had a lighting function but also a symbolic signification that raised in importance at the Christian period. Byzantine period lamps often bear a little cross. The lamps typology gives precious information about the chronology and eventually about the provenance (some of them come from Palestine). Generally, the lamps can be dated between the 1st and the 7th century AD.

|  |

| |||

|  | ||||

|

|

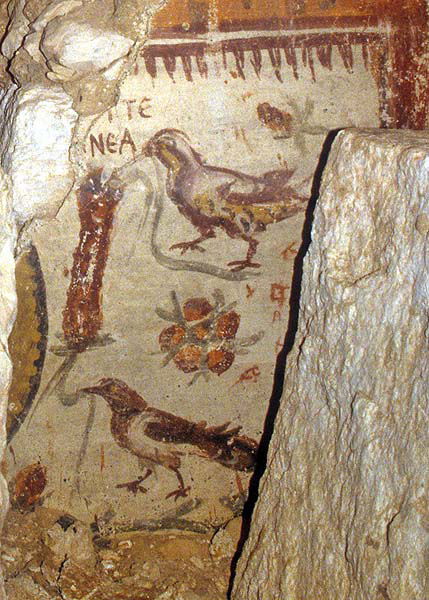

Several tombs contain painted inscriptions, almost exclusively in Greek language. The inscriptions may refer to the deceased but may also mention the name of the artisans who worked on the construction and decoration of the tombs. The most famous inscription found in Abila is the one written for Loukanios, telling: "Be confident, Loukianos, nobody is immortal. (1)4 years old":

photo by author

photo by author

The most decorated part of the tombs is the alcove in the bottom of the chamber, which is the prestigious location reserved to the most honoured family members. It is also the architectural element that is seen in first when entering the tomb, as well as the part which is lightened by the natural light coming through the open door. |  photo by author |

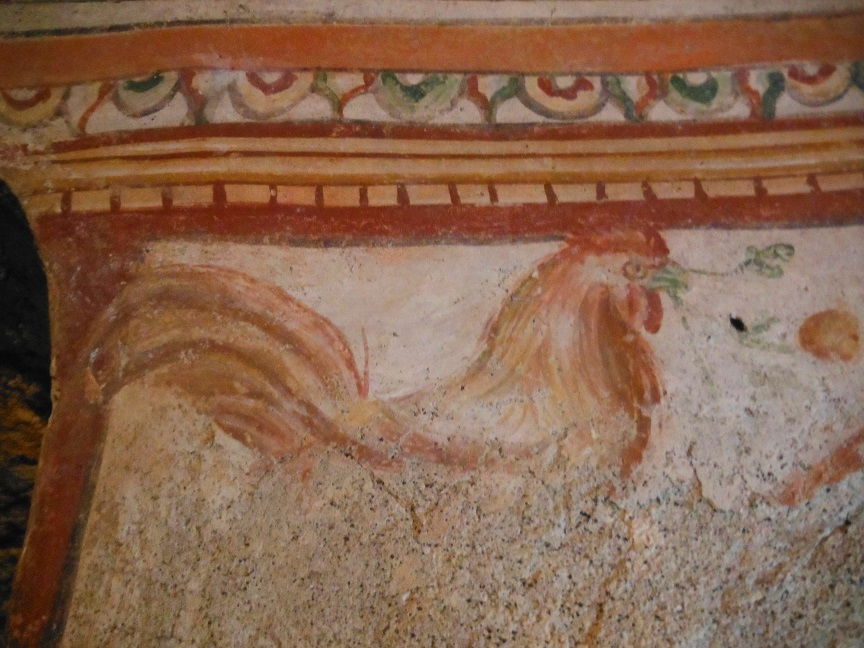

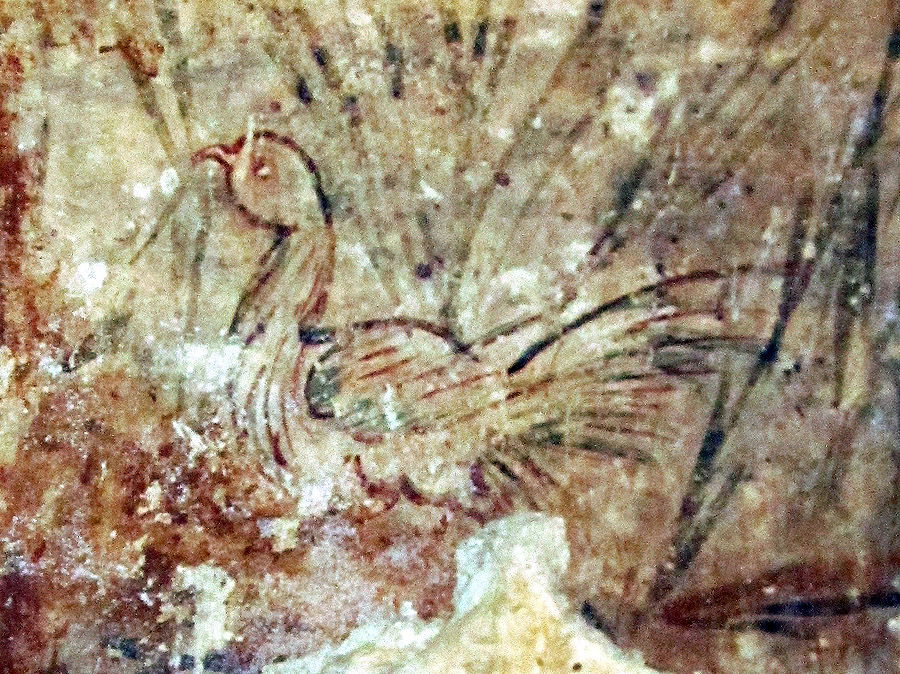

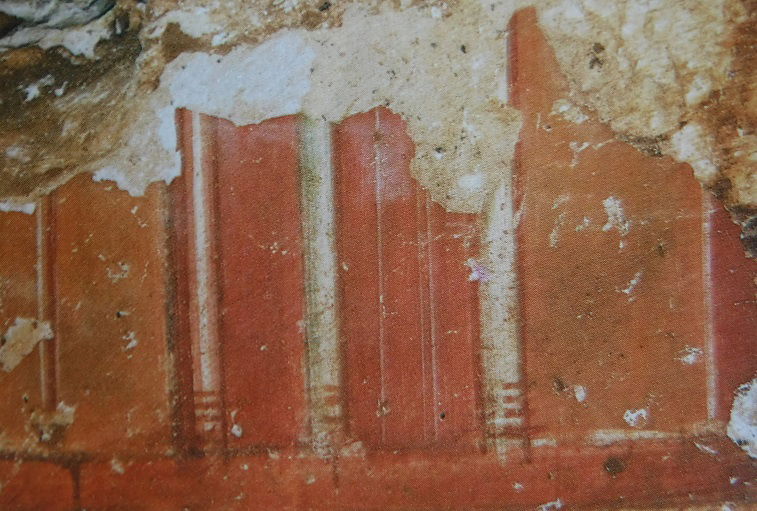

Abila's frescoes are of high interest. They include traditional floral and rural ornaments integrating animals (birds, rabbits...), geometrical patterns, imitation of marble, wreaths and strips, architectural motives as columns, candelabra, portraits, figures that refer to the Greek sacred or mythological background as cupids, satyrs, maenads, some wild animals and dolphins, all related to the Dionysian cult. Dionysios, better known as the divinity of grape and wine, was also associated to death and life, more precisely to the transition from death to life. Therefore, the Dionysian register is very common in the funeral iconography. (Some of the below frescoes are not existing anymore due to tomb looting after the excavations).

photo by author |  A. Barbet, C. Vibert-Guigue vol II pl.V |  |

A.Barbet, C. Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol II pl. IV |  A.Barbet, C.Vibert-Guigue, ref. below pl. 86 |  A.Barbet,C.Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol. II pl. II |

|  |  A. Barbet, C.Vibert-Guige ref. below, vol. II pl. II |

|  A.Barbet, C.Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol. II pl.20 |  A.Barbet, C.Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol. II pl.III |

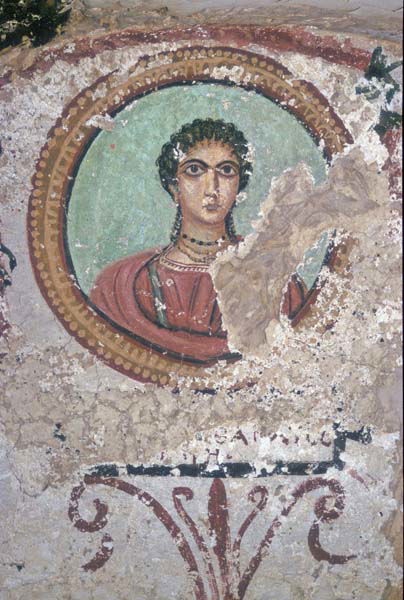

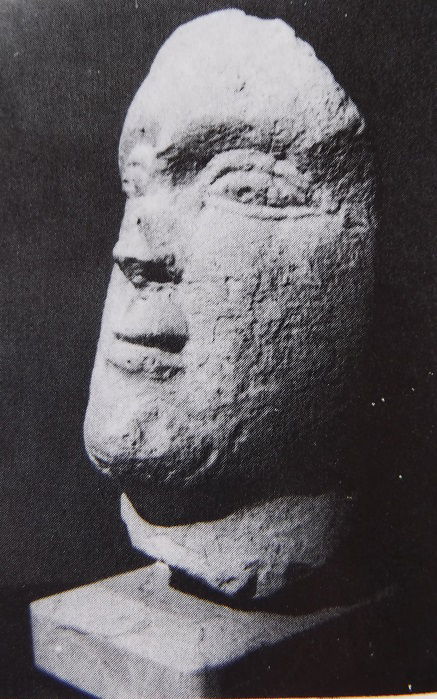

The deceased portraits probably represent the most touching iconography. Portraying was the privilege of the rich citizen and a limited number is preserved. It is impressing to see the realistic faces of people who were alive about 1500 to 2000 years ago! (Unfortunately, some of the below portraits have been ruined by the tomb robbers after the excavations)

A.Barbet, C.Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol. II pl.II |  A.Barbet, C.Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol. II pl.II |

However, some characters may not be the personally portrays of the tomb occupants but theater masks or maenads, in reference to the Dionysian theme. The following faces are thought to be theater mask (left) and/or maenads (center and right):

|  |  |

The below painting (Tomb Q1 Loukianos) is hard to interpret, either as a priestess (fringed shawl), a muse (tablet) or a house mistress (house key at the belt).... ( The right photo taken before the deterioration of the below part of the figure)...

|  |

...while those veiled women are maybe on the way to the world of Death:

|  A.Barbet, C. Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol. II pl. VI |

The allusions to the infernal world are effectively also present, with painted fragments of the god Hermes, the divinity who leads the souls to the Hells, as well as the symbolic personification of the Memory, Nemesis, associated to the griffons. We also find a certain number of sphinxes, traditional tomb custodians supposed to keep the robbers away. (The below relief has been ruined by tombs robbers after the excavations)

http://users.stlcc.edu/mfuller/abilaH60plan.html

http://users.stlcc.edu/mfuller/abilaH60plan.html

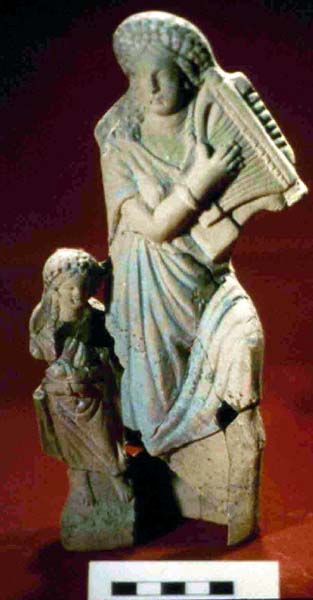

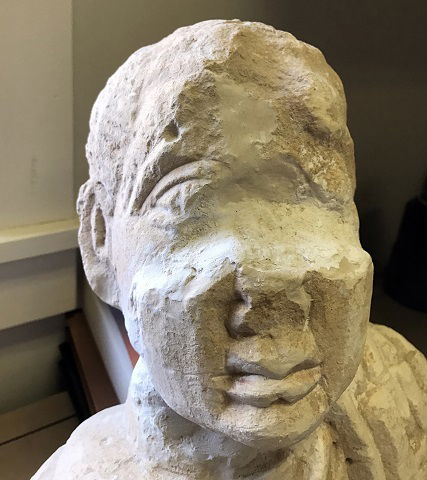

The archaeologists also discovered a large quantity of busts placed in the opening of the loculi, in the niches or maybe stuck in the ground. The most beautiful specimens have been probably stolen by the robbers. The busts that reached us are plus or less elaborate. Some of them are just rough sketches, others are stylized while some specimen show a quite personal physiognomy.

http://users.stlcc.edu/mfuller/abila/abila2017/Q10LoculiWithBustLg.jpg

http://users.stlcc.edu/mfuller/abila/abila2017/Q10LoculiWithBustLg.jpg

|  |  |  |  A.Barbet, C.Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol. I p. 332 |  A.Barbet, C.Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol. I p. 332 |

Surveys put in light a difference in the quality of the construction on one hand, and the decoration of the tombs on the other hand. Interestingly, we notice that a low quality in the construction goes together with a batched and poorly developed decor, as well as with the non-completion level. There is an apparent correlation between the financial power of the monument sponsors, the completion level, the decor elaboration and also the quality of the painting material used by the artists and the finesse of the works. The fully completed tombs have also the most beautiful designs as well as the most extensive colours. Some of the Abila's frescoes present a blue colour, which is really exceptional.

|  |

A.Barbet, C.Vibert-Guigue, ref. below, vol. II pl. VI | |

The archaeologists also noticed that there were two distinctive categories of artisans: on one hand, those who were in charge of digging or carving the places, closing the loculi with mortar and executing a rough decor. They were probably grave-digger and masons, had to be responsive to circumstances and work quickly. On the second hand, the decorators-painters, who had time to elaborate a careful work in consultation with the sponsors and families and were not pressed by the circumstances. Of course, the services of this second category were not accessible to all the social classes. However, a comparative survey of the painting style brings to light that the painters who worked in Abila where local artisans, probably trained in an hellenised centre of the area.

References:

Achim Lichtenberger: If the ‘Augustus of Primaporta’ Were a Coin: Classical Archaeology and Numismatics, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327225422_If_the_'Augustus_of_Primaporta'_Were_a_Coin_Classical_Archaeology_and_Numismatics

Alix Barbet, Claude Vibert-Guigue: Les Peintures des Necropoles Romaines d'Abila et du Nord de la Jordanie, vol. I and II, Beirut 1994.

Claire Bennett, Tanja Rathjen: Analysis of Abila, Jordan, from an Archaeological Point of View, http://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-126-2.pdf

David Chapman: Roman Remains at Decapolis Abila: an update on twenty-eight years of excavations www.poj.peeters-leuven.be

Lamia El-Khouri: Tombs of the Roman and Byzantine Periods at Barsina (Northwest Jordan) https://www.jstor.org/stable/41304084?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

W. Harold Mare: Abila of the Decapolis Excavations, June 30, 1991 https://www.persee.fr/docAsPDF/syria_0039-7946_1993_num_70_1_7324.pdf

W. Harold Mare: The Technology of the Hydrological System at Abila of the Decapolis, http://publication.doa.gov.jo/Publications/ViewChapterPublic/1260

Zeidun Al-Muheisen : Archaeological Excavations at the Yasileh Site in Northern Jordan: the Necropolis, https://journals.openedition.org/syria/487?lang=en

https://alchetron.com/Abila-(Decapolis)

Lectures:

David Vila: https://app.vidgrid.com/view/l14qczsLI2tb/?sr=yPaRLQ and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5FmjS3qQvnM&ab_channel=ACORJordan