The Mameluk empire ends in 1516, in front of the advance of the Ottomans who had already started their expansion from Anatolia since the 15th century. The Ottoman control over the area will persist till the beginning of the 20th century, except a break in the 18th century due to some incursions from Arabia, and then in front of the Pasha of Egypt. But the Ottomans take back the region at the beginning of the 19th century.

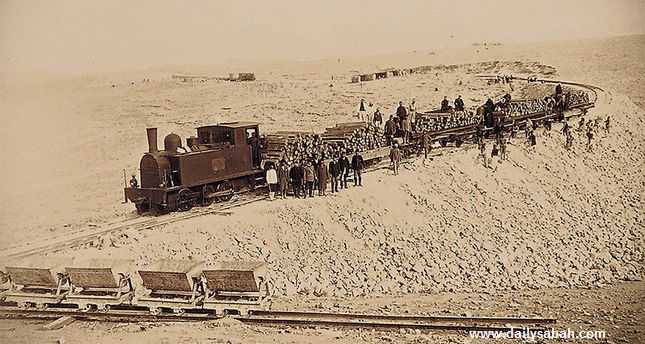

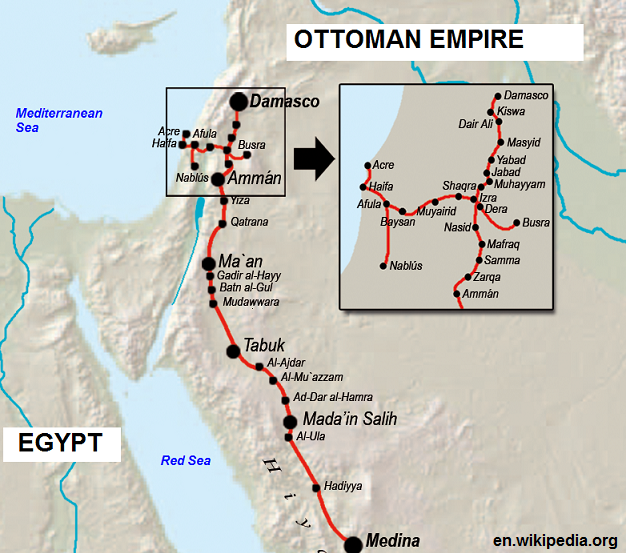

The Ottoman Jordan is administered from Damascus for its northern part, and from Egypt for its southern part. Ottoman authorities has little interest in these remote areas neighbouring the desert. They consider Transjordan only as a passage towards the Hedjaz region and Mecca. In order to protect the roads against Bedouin attacks, the Ottomans fortify them with military stations. It is henceforth possible to easily connect Damascus with Mecca. A series of forts are built or refurbished, some of them can be visited today: Qasr Shabib in Mafraq, the forts of Jizah, Qatraneh, Ma’an, Aqaba… other measures of security consist in armed camel riders escorts, who used to pay taxes to the local tribes to insure the security of the pilgrims cortege, all framed by the central administration. Later, the Ottomans built the railway of the Hedjaz, which allowed to reach Mecca faster, but also to easily transport troops to the South of the empire. In the 19th century, the Ottoman authorities undertake to organize territories and to develop the administration. They establish schools, exclusively for the Muslim population. They impose a cadastre, forcing many Bedouins to settle in order to keep their territory. They also vainly try to impose the Turkish language.

Construction of the Hedjaz railway in the Jordanian desert at the beginning of the 20th century  | Route of Hedjaz railway in 1914  |

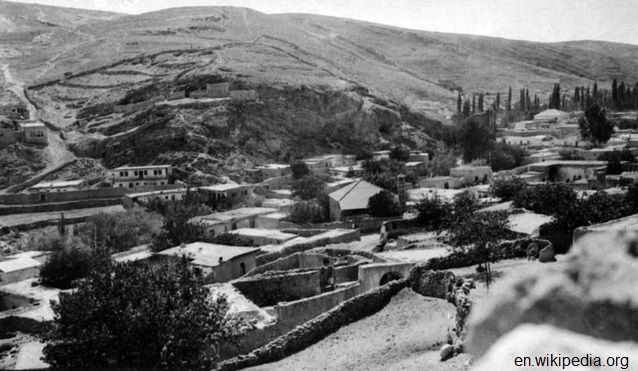

Urban centers emerged starting from the mid 19th century, as Irbid, Salt and Madaba. The city of Salt in particular is an excellent example of the urban development that operated around 1860. However, rural life kept holding the major place. The economy of the Jordanian countryside was essentially supported by the pilgrimage caravans, which constituted a real market for cereals, meat and burden beasts. There was also an important trade road from East to West, bringing goods to Palestinian cities, essentially Jerusalem and Hebron. Bitumen from Dead Sea was used as fuel and for animal remedies. Sulfur in the Jordan Valley was also exploited. The dwellers of the Syrian and Palestine cities used to come to Jordan for making trade and acquire items of pottery and glass, textiles and tobacco pipes. The trade was largely based on barter system.

The small city of Madaba is example of the Ottoman architecture and many houses of this period are still inhabited today. Salt city is also worth stopping by, although it needs a shot of renovation and maintenance… the exhibition at Abu Jaber house gives a good information about the life at the Ottoman time. Salt old houses have been built by merchants enriched through their trade in Mediterranean till Italy. Therefore, they are representative of a fairly high class. Um Qais archaeological site also protects an Ottoman village, erected over the antique settlement. Moreover, a little everywhere over the Jordanian countryside and in small villages, we can see houses of that time, often abandoned. Almost all villages keep in their historic centre some buildings or remains of this period. Moreover, amateurs of railway could stop at the small Amman rail station, or go to admire the new renovated locomotive at the Wadi Rum station.

Salt, Abu Jaber House

At the dawn of the 20th century, internal tensions appear throughout the empire, adding to the Western colonialist appetites. The Ottoman Empire falls in pieces. It has lost a lot of territories that it used to handle at its apogee. The state accounts are crumbling, some regions are ravaged by famine and epidemics. The World War I will precipitate its downfall.

View of Amman in 1918